Taste, Time, and the Tools That Hold Us

On AI, abundance, and the quiet power of idleness

“Nature does not hurry, yet everything is accomplished.”

— Lao Tzu

Reimagining Abundance in the Age of AI

I’ve been returning to the idea of abundance—the central tension of this Substack—as it increasingly defines how we frame technological progress and venture-scale ambition. Peter Diamandis, in his 2012 TED Talk discussing Abundance, imagines a future in which exponential technologies transform scarcity into surplus, declaring that “providing abundance is humanity’s grandest challenge.” His vision is now echoed across a growing cultural and intellectual current: Andrew Yang’s “Abundance Agenda”, Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson’s Abundance, Misha Chellam’s Abundance Network, and David Friedberg’s thesis at The Production Board.

Yet, as Richard Heinberg cautions, our pursuit of limitless growth often blinds us to the ecological boundaries we must respect. He writes, "Humanity's confrontation with limits will make this century pivotal."

In much of today’s discourse, abundance is framed through the lens of technological capability and economic efficiency. David Friedberg, on the All-In Podcast, regularly outlines a vision in which AI and automation enable a 30-hour workweek, freeing up time for family, creativity, and leisure. It’s a vision that echoes a recurring thread here at Circular Architect: as AI becomes more intelligent, humans are afforded the opportunity to become more human—and maybe that means more leisured, more intentional, more tasteful, more communal.

Still, this promise invites deeper inquiry: What do we actually do with that time? How do we ensure that the tools designed to serve us don’t end up shaping us more than we shape them?

AI as Tools, Not Masters

The rapid integration of AI into daily life represents both a promise and a peril. Every day, we’re confronted with the dizzying pace of advancement in new tools, streamline operations, writing code, and even generating art and adverts. But a widely circulated LinkedIn post by Manuel Kistner recently stopped me in my scroll. He draws a striking parallel between the subsidized rise of Uber and the current affordability of AI: we’re living through AI’s 2015-Uber moment—addicted to cheap, frictionless power without grasping the long-term costs.

In the short term, AI democratizes capability—a founder and two engineers can now achieve what once took a team of fifteen. But what happens when the subsidies end? What happens when value-based pricing kicks in, and the $20/month tool becomes a $20,000/year necessity?

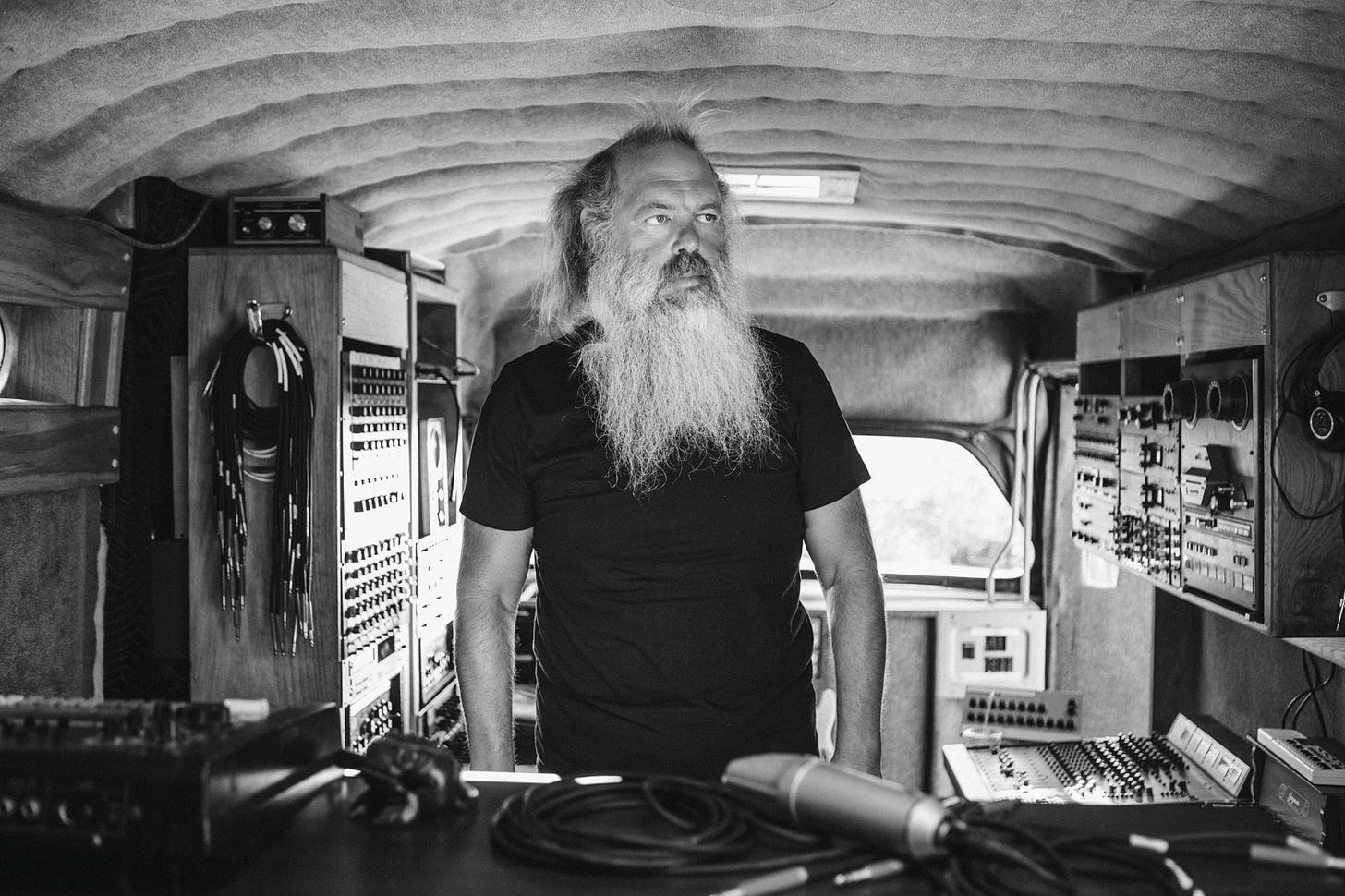

Rick Rubin, in The Creative Act: A Way of Being, reminds us that tools are only as powerful as the intentionality behind their use. “Intention is all there is. The work is just a reminder,” he writes. In an age of generative everything, we must reclaim authorship over our tools. If AI becomes a crutch rather than a collaborator, we risk not only outsourcing labor—but also curiosity, learning, and identity. For a complementary perspective through the lens of design practice, A Designer’s Guide to Engaging with AI by Carly Ayres offers a compelling continuation of this conversation.

Restoring the Value of Idleness

Our cultural obsession with productivity has left little room for idleness in conversations about AI—a state too often mistaken for laziness rather than what it truly is: a necessary space for rest, reflection, and creative incubation. In true idleness, strange connections form and deep integrity takes root.

As Jessica Hische shares in her interview on Carly Ayres’ Substack, AI can be a “superpowered thesaurus”—a helpful collaborator, not a replacement. She still draws by hand. She still builds with intention. The point isn’t to reject the tool; it’s to become most visible through it—to let your creative fingerprints remain unmistakable, even in collaboration with machine intelligence.

The Taoist notion of wu wei—effortless action in harmony with nature—offers a countercurrent to hustle culture. What if progress wasn’t about faster, cheaper, more—but about truer, deeper, wiser?

This ethic is echoed in Mandy Brown’s recent musing, Toolmen, where she warns against collapsing every inefficiency with AI. When all work becomes solitary and systematized, we lose the social seams that make creation human: the hallway conversation, the shared frustration, the creative friction. AI makes it possible to create alone—but should we?

Meanwhile, Erik Rittenberry of Poetic Outlaws names a deeper paradox: in designing a life of ease, we’ve also designed out struggle—and with it, meaning. His critique of “gluttonous comfort” isn’t a rejection of progress, but a warning that convenience, taken to its extreme, dulls the edge of aliveness.

But comfort need not negate meaning. This isn’t a binary between optimization and obsolescence, between hustle and helplessness. Two things can be true: AI may make life easier, but that doesn’t mean we’re excused from depth. In fact, the time it frees could be our greatest resource—if we use it well.

Even in a culture of overload, idleness has its place—not as distraction or numbing escape, but as a spacious, generative pause. It’s in those quiet, unscripted moments that new meaning takes root. To be idle is to resist the twin pressures of optimization and consumption. It’s not indulgence. It’s invitation. It’s resistance. And it might just be the soil where post-AI purpose begins to grow.

Meaning, Resistance, and Creative Integrity

If AI gives us more time, the question becomes: what will we do with it? The deeper invitation here isn’t just to work less—it’s to work differently. To root our creative energy in meaning, not just efficiency. To treat time not as empty space to be filled, but as soil to be cultivated.

Erik Rittenberry calls out our cultural malaise with cutting clarity: “The comfortable life is killing you.” But the antidote to comfort isn’t suffering for suffering’s sake. It’s returning to what makes us feel alive—challenge, purpose, connection, story. If we dull every edge of difficulty, we also sand down the meaning that comes with it.

Even venture capital is undergoing this redefinition. The best investors today don’t just offer capital—they offer community, identity, myth. As I wrote recently in my Substack, venture is no longer just a financial instrument—it’s identity work. It’s modern myth-making. It’s a bet on human ingenuity, yes, but also on human story.

What we need is not more tools but better questions. What kind of humans are we building with our tools? What values are embedded in our architectures of scale? Who gets to build, and who gets displaced?

These are the questions we must ask if we hope to steward abundance wisely.

Toward a Flourishing Future

Abundance is not merely material. It fundamentally begins (and ends) with production capacity—namely, energy abundance and resilience (more on that later)—but it must also be spiritual, relational, and ecological. A future worth building is one in which technology expands our capacity to imagine, to care, to belong. Where AI doesn’t extract from the human spirit but partners with it. Where progress is measured not in acceleration, but in intention and depth.

As Rubin reminds us, it’s not about doing more. It’s about doing what matters.

The wind must still blow. The tree must still bend. And we must still build the stress wood that lets us stand.